Predicting the impact of climate change on population size

Predicting the impact of climate change on population size

It's an established fact that the way many species behave, their appearance and their weight are affected by climate change. "We tend to assume that such changes are bad for animals and plants", says Martijn van de Pol. "But in most cases, we can't tell if and under what circumstances their population numbers actually decline." And for conservationists and policy makers, a strong decline - or indeed a strong increase - is the only relevant criterion.

Without reliable research on the impact of climate change on population dynamics, any measures taken to protect species may be premature or inefficient. In fact for many species, even our basic data is scant or incomplete. So how to proceed? Van de Pol and his PhD student, Nina McLean from The Australian National University, found a solution together with colleagues from the British Trust for Ornithology and NIOO.

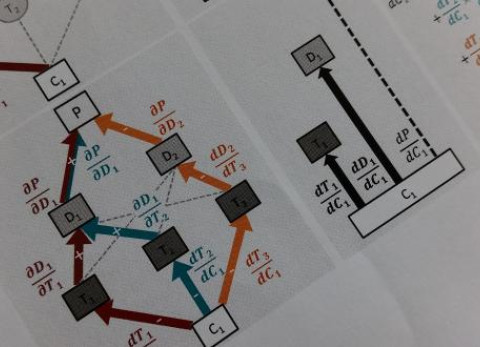

"We have developed a method that allows us to test what types of animals are most affected by climate change in terms of their population numbers, even if we have just a limited amount of field data to work with", he explains. Only limited funds are available for conservation measures, so establishing which species need such measures the most is important. "We need general rules for the impact of climate change, so that we can prioritize more effectively."

So what species are most at risk? Long-living species? So-called 'habitat specialists' that depend on a very particular natural environment? Finding the answer to those questions will be the next step for the researchers. They have already done some pilot tests using data from 35 species of British woodland birds over the period 1966-2013. That's no coincidence: there is a lot of data available about bird species, relatively speaking, even though it's still by no means complete.

The data showed that some birds were prompted by warm springs to lay their eggs earlier in the season, while others did the exact opposite. Late-laying birds tended to have fewer chicks, but in most cases the overall population size was not affected significantly as other factors attenuated the impact. More interesting was the question for which species population numbers did decline due to changes in the timing of their egg-laying.

Earlier studies had suggested that species with only a single brood per year were quite vulnerable. The new method confirms that the number of broods is indeed a good indicator for climate-sensitivity, albeit for a different reason. And it's something we can also apply to species we know relatively little about: we no longer need detailed accounts of the date and success rate of their nests or the changes in their population size.

The research team have in the meantime embarked on another round of tests, using a larger data set from the Netherlands, courtesy of NIOO's Centre for Avian Migration and Demography. Van de Pol: "We're talking about some fifty species of birds, more than 200,000 animals. What are the effects of changes in their weight on their survival and the number of birds that make up the population? We can't wait to find out!"

With more than 300 staff and students, the NIOO is one of the largest research institutes of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (KNAW). It specialises in terrestrial and aquatic ecology. As of 2011, it is located in an innovative and sustainable research building in Wageningen.

For more information:

- Froukje Rienks M.Sc., Science Communication Officer NIOO-KNAW, tel. +31-6-10487481 / +31-317-473590,f.rienks@nioo.knaw.nl

Paper: Predicting when climate-driven phenotypic change affects population dynamics, Nina McLean, Callum R. Lawson, Dave I. Leech & Martijn van de Pol, Ecology Letters (2016) 19: 595–608