Micro-organisms too can cooperate and rewild

Micro-organisms too can cooperate and rewild

Press inquiries

From insignificant individual cells to a rich community full of cooperation. That is how our understanding of the micro world of bacteria, fungi and other microscopic organisms has developed over the past two decades. This “microbiome” that exists on leaves and roots, for example, and in the gut and soil, has an enormous impact on the environment. Researchers at the Netherlands Institute of Ecology (NIOO-KNAW) are looking at functions such as the “consumption” of greenhouse gases, communication through scent and assistance to endangered plants.

‘Ten to twenty years ago, you were essentially studying a few isolated microbes,’ says Jos Raaijmakers. Since 2014, he has been head of the Microbial Ecology department at NIOO. Raaijmakers has seen how research techniques have developed rapidly since then. This revolution began with the mapping of entire communities using DNA codes, rather than just a few cells and a limited number of species. ‘At the time, it was still like collecting stamps: what species are present? We were finally able to find out more about this, because the vast majority of micro-organisms cannot be cultivated in the laboratory. Nowadays, we focus much more on what these micro-organisms do. And especially what they do together.’ This has been made possible by increasingly advanced sequencing methods: DNA codes can now be read almost instantly from, for example, a soil or leaf sample.

Its own coat

Every place has its own microbial community: its own microbiome. For example, a plant leaf has a whole coat of certain types of bacteria and fungi, called the “phyllosphere”. The leaf of another plant, around roots (in the “rhizosphere”) or in intestines, has a completely different composition. Raaijmakers: 'There are very few species that thrive everywhere.' Although fungi and bacteria still have a bad reputation, most of them actually have neutral or even beneficial properties. Only a small proportion are pathogens, and even that depends on the situation.

‘All organisms are completely covered with microbes. The interesting thing is that everyone assumes that they always have a function. But research shows that only in some cases is there a demonstrable function for the host.’ To find out what this means for plants, you can grow them in the presence and absence of the corresponding microbiome. Growth, disease resistance and root architecture provide clues about the effects that microorganisms have on the plant. It's not black and white. ‘They may only determine 5 per cent of the plant's final appearance, and in another case, for example, 30 per cent. And sometimes not at all: then it is the plant genes that leave their mark. There is still a whole puzzle to be solved here.’ Raaijmakers argues that this should always be the starting point for research into a specific microbiome. ‘If the microbiome turns out to play only a very small role, is it still worth further research?’

Classic & modern

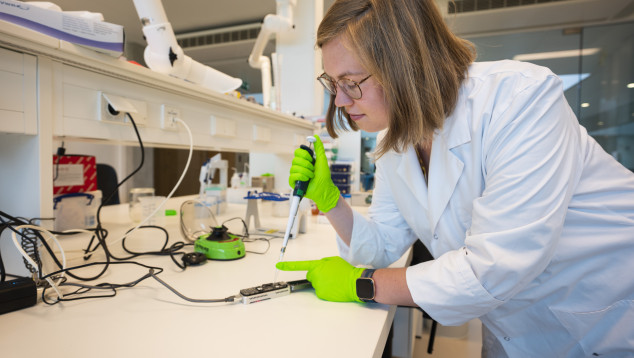

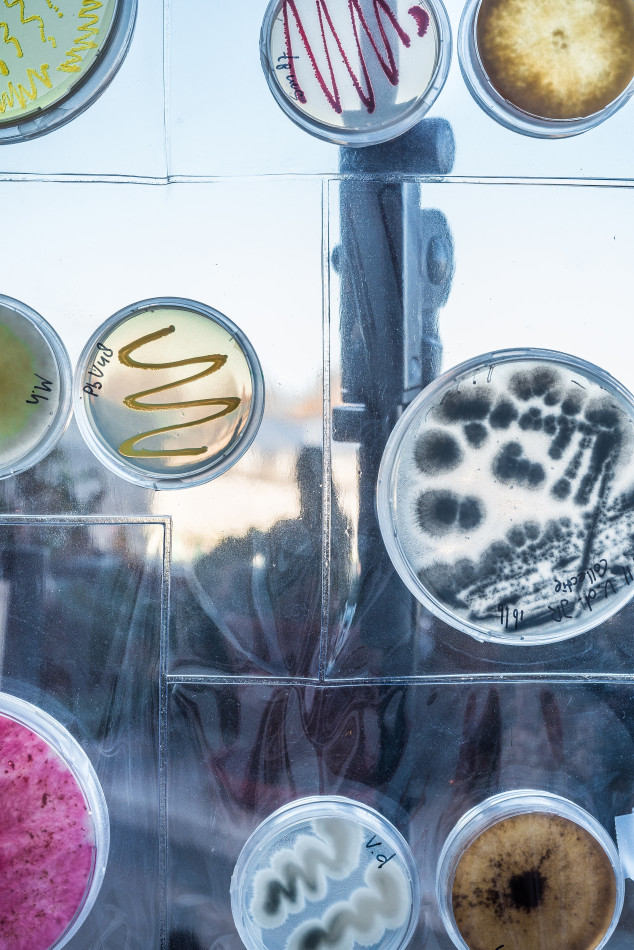

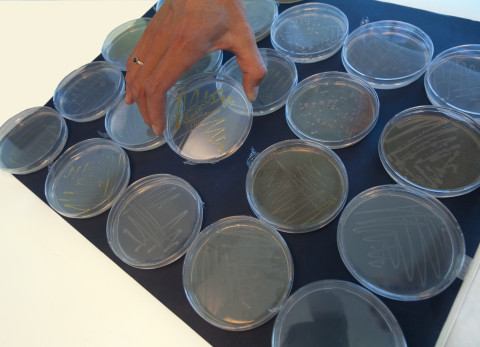

Back to the beginning: how did microbial research start? The classic approach involves isolating bacteria and fungi from the environment, microbiologist Paul Bodelier explains. ‘You look at what grows on a particular culture medium in the lab and select individual colonies of a particular species. You can then use these “isolates” to test what they are capable of. We have now built up a huge collection of isolates.’ The DNA techniques that make it possible to view microorganisms as a community required a lot of trial and error in the beginning. The PCR (polymerase chain reaction) technique originated in fundamental DNA research, but proved to be very important for ecology in the early 1990s. That is why NIOO started its own DNA lab at that time. ‘By amplifying the so-called “16S” gene with PCR, you can see which microorganisms are present in your sample. At that time, it was still about species diversity. You really only saw what you knew, because that's what you amplified with PCR.’

Gradually, ecologists began to look at the rest of the DNA, searching for functional genes that reveal what micro-organisms are capable of. The first “genomes”, the complete genetic code of organisms, became available. The next step was that of the metagenomes: the code of an entire community in, for example, a handful of soil. This required increasingly better sequencing and analysis methods, these did get developed.

‘With shotgun metagenomics, you break down the DNA in your soil sample into small pieces and then read those codes. Using special programmes, you can virtually stick these pieces back together to form entire genomes, which contain all kinds of information that we didn't yet know from any of the genome databases. We can now characterise many more microbes, including species that we couldn't grow in the lab. So we've really gained a better understanding of communities and their functions.' This is much more difficult with fungi, which have much larger genomes, than with bacteria.

Hello!

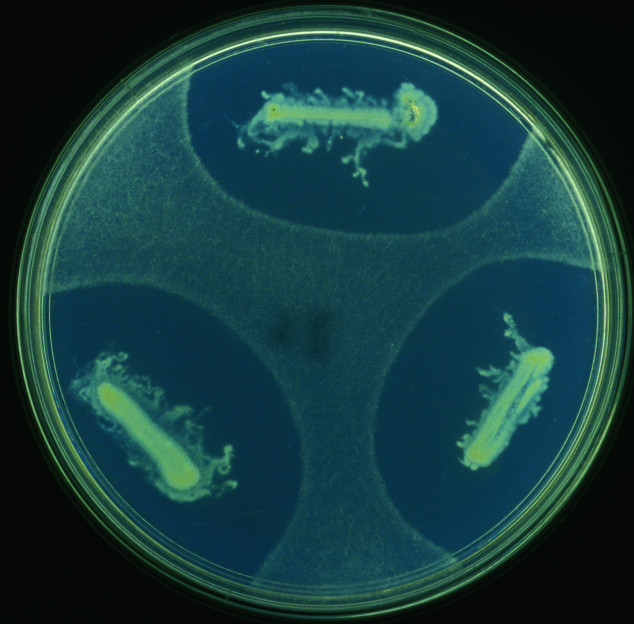

Microorganisms must communicate with each other in order to interact within the microbiome. How does this work? Paolina Garbeva has been researching this for years at the Department of Microbial Ecology. Messages between bacteria (“come here too”), but also between bacteria and fungi (“stay away, this food is mine”) are conveyed through scent. These spread quickly through water or air.

These communication substances are essential in nature, but also very interesting for humans. For example, almost all antibiotics that we use as medicine originally come from microorganisms in the soil. These are substances that are used in nature for “chemical warfare” between competitors. By bringing together isolates of different microorganisms in the laboratory, you can discover and follow such interactions.

Beyond combating plant diseases

‘Actually, the common thread running through the story is that we always come back to the classic method. Despite all the advances in DNA techniques, because those only give you the genetic material and you don't have the organism itself,’ explains Bodelier. And if you want to test the functions of micro-organisms, there's only one way to do it: with the organism itself.

When it comes to soil, there is virtually no technique for measuring the functions of micro-organisms directly in the environment without disturbing it. NIOO researchers are now combining the traditional and modern approaches. First, they use DNA techniques to “screen” what kind of micro-life is present in a given location, then they use traditional methods to isolate it, and finally they return to the field to see whether the isolate has the same interesting or desirable effect that the researcher observed at the start. Bodelier: “This research is now progressing quite rapidly: from start to finish in five years, for example. This has been achieved in the Promise project.” That project revolves around an agricultural application, where root microbes are used in sub-Saharan African countries to combat a serious weed in the sorghum cultivation of small self-sufficient farmers.

The isolation of micro-organisms is now much more targeted than in the past, allowing us to examine their properties and identify those that are of interest more quickly. ‘It is no longer just about applications for sustainable agriculture – such as combating plant diseases – but also about the climate, healthy soil and clean water. Steering things in the right direction is becoming increasingly within reach. Adding a specific organism to a particular location is one approach, but looking at what is already living in the field and how you can make it work better is perhaps more promising.’

Ecological questions

What major ecological questions could this answer? Bodelier himself studies the micro-organisms that produce or break down greenhouse gases such as methane and nitrous oxide. However small they may be, they have an enormous impact on global greenhouse gas production. He has recently started looking at the changing methane balance in the Arctic lakes of Greenland, and has for much longer been studying what kinds of methane-producing and, above all, methane-consuming bacteria are active in compost. In a new study, compost is also being added to the soil – with or without clay – to monitor what happens.

This research has a clear link to soil policy. ‘The EU’s new Soil Monitoring Act finally takes living soil seriously, with an integrated approach to healthy soil. But now the microbial component still needs to be given its rightful place. The fungus-bacteria ratio, which compares the biomass of both groups, is being applied. In undisturbed forest soils where a lot of carbon is sequestered, you see relatively more fungal mass, and where carbon is consumed by growing crops, there are more bacteria. Microbial diversity is more difficult to measure, yet it is declining due to intensive land use.'

Wild microbiomes

What other roles do microbiomes play in ecosystems? Raaijmakers and his team conducted research on the wild relatives of plants such as tomatoes. ‘Because the original soil microbiome of wild ancestral plants is no longer present in cultivated crops, these plants are much more susceptible to insects.’ This knowledge can be valuable for making agriculture more sustainable, but it also tells us a lot about the role of the microbiome in natural ecosystems. Think, for example, of the reintroduction of plant species and the management of agricultural land that has been taken out of production.

‘There have been interesting developments in ecological ecosystem restoration over the past three years or so,’ says Raaijmakers. ‘Especially with plants the microbiome can be taken along. This improves the germination and establishment of endangered plant species. In this way, you can increase the chances for the plants in the most sensitive initial period.’ The rewilding of the microbiome can thus be extended to the rewilding of the entire ecosystem: if you want to reintroduce a tree or other plant species, you also need the corresponding microbiome. 'If you provide the right combination of microorganisms with which they have good evolutionary alliances, you give those plants a head start.“ You provide them with 'microbial friends”.

Soil researchers at NIOO have applied this in nature. Using soil transplantation, they demonstrated that microorganisms in donor soil from healthy heathland or other nature reserves can quickly improve less healthy soil. And in the “Ecosystems of the Future” containers in the NIOO experimental gardens, the focus is on plants that are moving to more northern regions due to climate change, without their microbial friends and enemies. Will they proliferate, and will you end up with the same or a whole new ecosystem?

What remains to be investigated?

‘I would like to make the functions of the organisms in the microbiome even more visible,’ says Raaijmakers. ‘There are genetic traits that you will never see in the laboratory, but you will see them in nature. What triggers are needed to bring them out in laboratory research?’ ‘Microbiome research has taken off enormously. Now we need “success stories” that make the possibilities for nature restoration or sustainable agriculture practical and visible. If you really want to reduce pesticides and other uses of chemicals, you need to know how to consistently apply the composition of the microbiome.‘ Raaijmakers goes on to say that "with what are now called synthetic communities of microorganisms, you can reconstruct a desired appearance of a plant – growing well or not diseased, for example – that is linked to that microbiome. There are between fifty and sixty different types of microbes in there. There is no single silver bullet, no single type of microorganism that protects crops or wild plants against everything. It is clearly a team effort."

What else lives there?

Bacteria and fungi form the bulk of microbial research. ‘We don't know exactly how many species there are, but we do know that there are a lot. For example, the estimate is that only 1 per cent of bacterial species have been identified and described. That means there are probably more than a billion in total,’ explains Bodelier. A single gram of soil contains billions of microorganisms, including several thousand species of bacteria and fungi. But other organisms also have their place in the microbiome.

The outliers that we often forget are viruses (see box on page 15). Then there are protozoa – all kinds of single-celled organisms, including “mini predators” – and Archaea. These were previously dismissed as primitive bacteria because of their superficial resemblance. We now know that they form their own group, from which humans are also descended. Because they are very difficult to cultivate and grow very slowly, not much research is being done on them. Yeasts have the best reputation. Thanks to bread and beer, they have much better PR than microorganisms in general. Viviane Cordovez and her research group are looking at yeasts on leaves. Can a mixture of beneficial yeasts suppress diseases in wheat? They may be able to keep parasitic Fusarium fungi – which they have dubbed “cereal killers” – under control. Another branch of the research looks at the invisible biodiversity on the Galapagos Islands. The aim is not only to better understand the evolution of the different species of microorganisms, but also of the plants on which they live. Knowledge about the endangered native “giant daisies” and their unknown microbial friends may hopefully help to protect these plants.

Forgotten viruses

'In a lot of nature research and management, plants, animals, and microbes are normally included, but viruses aren’t,' says virus researcher Mark Zwart. 'Even though they definitely play a role in the health, dynamics, and ultimately the resilience of ecosystems.' Historically, attention has mainly focused on pathogens that affect humans, crops and livestock. But all species – from plants to insects, fungi and mammals – carry viruses, and a viral infection does not always lead to disease. In many cases, they appear to have beneficial effects, such as increased drought resistance in plants. 'And even when viruses do cause disease, the effect at the ecosystem level can be positive. For example, viruses can safeguard diversity in microbial communities by slowing down the fastest-growing species.'

What concerns Zwart is that we know very well where plants and animals occur and why, but virtually nothing about viruses. ‘I want to understand how viruses develop and spread in natural ecosystems, and how virus communities change in space and time. And what that means for the evolution and resilience of ecosystems.’

How do we expose this hidden world of viruses? Viruses are smaller than small. They are minuscule parasites that consist only of genetic material in a protein shell. Nowadays, modern sequencing techniques can be used to map all the viruses present in an organism or environment at once: the virome. However, this is still not easy. ‘For bacteria and fungi, there are ready-made methods for characterising their communities, but for viruses this is technically much more difficult due to their enormous genetic diversity. This often makes it difficult to recognise which genetic material actually comes from viruses.’ Nowadays, you can use machine learning analyses for this, which utilise knowledge about virus characteristics or recognise patterns that are invisible to us. 'This allows us to detect viruses that we would have missed in the past. What's more, we can use new statistical methods to link virome data to ecological data, such as soil type, plant species or season.

This is the ninth and final article in a series on 70 years of ecological research at the Netherlands Institute of Ecology (NIOO-KNAW). Every edition featured another line of research. Find out more about 70 years of ecology here.

This article also appeared in the December issue of Vakblad Natuur Bos Landschap.