Under the bird ring's spell

Under the bird ring's spell

Ringing of wild birds has become indispensable as a research method to track individual birds. Since 1911, some 16 million birds have been fitted with a metal ring in the Netherlands. What has that brought in terms of knowledge, protection and policy? And what do new tracking techniques add? We dive into the world of meadow birds, goose visits and infectious diseases.

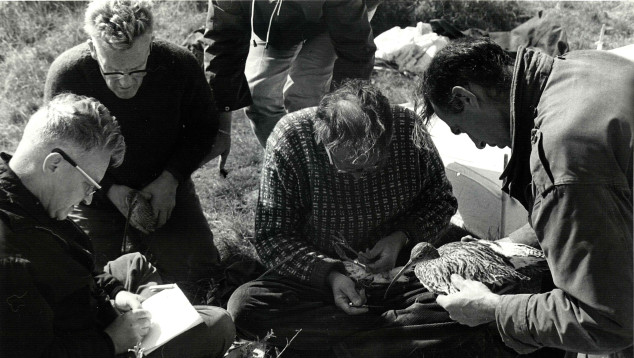

For more than a century, birds have been fitted with a light metal ring to track their movements. The coordination of all that ringing work lies with Dutch Centre for Avian Migration and Demography (Vogeltrekstation). This centre has been part of the Netherlands Institute of Ecology (NIOO-KNAW) for seventy years and has been a joint venture between NIOO-KNAW and the Ringers Association since 2006. This ‘scientific infrastructure’ allows nearly six hundred volunteer ringers and professional ornithologists to collect data for research, policy and conservation. Research has since expanded. In addition to ringing, all kinds of new tracking techniques have come into fashion, such as light loggers and GPS transmitters. In addition, today the collection of demographic data - reproduction, survival, immigration and emigration - is an important goal to better understand the dynamics of bird populations under the influence of, for example, climate change, changing land use or urbanisation. In recent years, we also want to know more about migration routes in relation to the spread of infectious diseases, such as avian flu and West Nile virus. In this way, the network of bird ringers is used again and again for current research questions.

Centralised organisation

Vogeltrekstation is the only organisation in the Netherlands to have a continuous framework licence from the ministry through which individual ring authorisations are issued. It is important that there is one central organisation that issues the uniquely numbered rings with the standard text ‘Vogeltrekstation Arnhem Holland’ and collects and manages the data so that it does not get fragmented or lost. After all, birds do not keep to borders, and ringed bird reports literally come from all over the world. Vogeltrekstation regulates the flow of data and ensures that researchers can track ‘their’ birds. In the process, researchers and citizen scientists work intensively together. The beauty of working with the volunteers, the citizen scientists before that term was in use, is the enormous enthusiasm with which they dedicate themselves to research. For them, ringing birds is a passion, a way-of-life. The expertise of many volunteers is not inferior to that of bird researchers, and their stamina to collect data in a standardised way year in, year out is admirable. The national scale and decades of research would be impossible to sustain with paid staff.

Migration: from Museum of Natural History to NIOO

Ringing wild birds for research began even before the (N)IOO was established in 1954. In 1911, Meindert Menno van Esveld provided a young starling in Nijkerk with a metal ring. Like many other amateur ornithologists thereafter, he answered the call of Dr Van Oord of the Museum of Natural History in Leiden. Reports of ringed birds poured in and provided important information on bird migration. At the time, hardly anything was known about this phenomenon. Observation stations were set up throughout the country for bird migration research. One of these was the Stichting Vogeltrekstation Texel. However, the station was active along the entire Dutch coast. In 1954, the research of the Stichting Vogeltrekstation was given a more solid basis when it became part of the new Institute for Ecological Research (IOO) of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (KNAW). Until 1962, the bird migration department remained in Leiden, then moved to the new research building in Arnhem and in 1980 to Heteren. Vogeltrekstation collaborates with organisations such as Erasmus Medical Centre and Sovon for a lot of the research. After NIOO's latest move to Wageningen in 2011, it also collaborates a lot with Wageningen University & Research. www.vogeltrekstation.nl

How does the ring system work?

Each bird ring has a unique number and states which ‘ringing centre’ it comes from. For the Netherlands, this is ‘Vogeltrekstation Arnhem Holland’. When a ring is applied, data are recorded about the bird (species, sex, age, measurements), ring location and ringer. All information is stored in the Vogeltrekstation database. Recaptures of live birds and dead birds found with a ring are reported from all over the world by ringers and the public. All these reports enter the database; the recorder and the ringer are notified. Especially larger bird species sometimes wear more visible rings besides the metal ring, which can be read with a telescope or binoculars. Almost every country has its own ringing centre that can send and receive ring data. Many ring data of birds reported back worldwide are also exchanged through the umbrella organisation EURING. More and more often, reports are completed via the website of Vogeltrekstation or a ringing centre abroad. But mail addressed solely to ‘Vogeltrekstation Arnhem Holland’ also still arrives, even from abroad.

Standardised ringing

Catching and ringing wild birds requires great expertise. You get a ringing licence only after an extensive two-year training course and an exam at Vogeltrekstation. Ringers today work in standardised research programmes, divided into individual ringing projects, which collect data on bird movements and demography. The flagship programme is the Constant Effort Sites (CES) programme, for which ringers collect information on the demography of general songbirds. Each year, ringers capture songbirds at over 40 sites according to a strict protocol. This has been done since 1994 and even longer in some other European countries. The ringing data provide yearly indexes of survival and reproduction of common birds. This provides insight into the underlying mechanisms behind changes in bird populations. Because the CES programme is implemented in the same way in many European countries, it lends itself ideally to research on large-scale changes due to, for example, climate change, changing land use or urbanisation. CES data therefore form the basis of several overarching European research projects.

For the rarer species, there is the Recapturing Adults for Survival (RAS) programme. In each of over three hundred RAS projects, one bird species is studied. Many projects are long-term population studies in which various aspects of reproduction and survival are measured annually. In addition to metal ringing, colour rings, which can be read with binoculars or telescopes, are increasingly used, facilitating the collection of follow-up observations without the need to recapture the birds.

Navigation and orientation

One fascinating question keeps popping back up: how do all those billions of migratory birds find their way every time? Back in the 1950s, Vogeltrekstation researcher Ab Perdeck made a major contribution to understanding birds' orientation and navigation abilities with the largest displacement experiment in history. Together with the bird ringers around The Hague, Perdeck fitted more than 11,000 starlings with a metal ring during their autumn migration, and then moved the birds to Switzerland. Thousands of other ringed starlings were not moved and formed the control group.

The control starlings flew to northwest France and England as usual. But young displaced starlings continued to fly in the original direction and were reported back from France and Spain. Displaced adult starlings did seem to be aware of their displacement and found their way back to the wintering grounds in France and England that they already knew. Perdeck concluded that while young starlings can orientate themselves, they cannot navigate: they cannot reach a predetermined target from any location.

Over seventy years later, Vogeltrekstation is repeating this research, with starlings now carrying a transmitter in addition to a metal ring. This allows us to observe in much more detail how the birds respond to the movements. Perdeck's conclusions largely stand, but there also seem to be deviations from the rule he discovered. There will be follow-up research for that.

Meadow birds

Almost all long-term meadow bird studies are part of the RAS programme. Generally, these projects are carried out in cooperation with land managers, agricultural nature associations and bird watchers. They are a crucial complement to more traditional nest protection and have contributed significantly to our knowledge of the bottlenecks facing meadow birds. The common thread in all these studies is the observation that the survival of chicks is almost everywhere too low to keep populations stable. The research confirms, that only where management focuses on reduced fertilisers and/or water level elevation - combined with delayed mowing - the chicks have sufficient chances of survival.

Consequences of bird flu

The RAS projects on sandwich terns contribute to mapping the consequences of the bird flu epidemic that swept through these colonies. Using the ring data that has been collected from nearly all colonies for years, population models are created to reconstruct the demographic consequences of mortality. From these, it is possible to predict how long it will take for populations to recover. For a long-lived species like the sandwich tern, this can easily take more than a decade. There are rays of hope, too. Observations of colour-ringed terns that previously tested positive for the virus show that some of the birds survive the disease and re-establish themselves as breeding birds the following year, although often in a different or even entirely new colony.

The RAS project on the peregrine falcon population also provides a lot of information on the impact of avian flu. Mortality among peregrine falcons due to avian flu infection is high. Recent analyses of ring data show that survival of adult and immature peregrine falcons fell sharply between 2021 and 2022, resulting in a rapid population decline. Both examples illustrate the enormous vulnerability of long-lived species with small population sizes. Ironically, the species now taking the hard knocks are exactly the same as the species decimated in the 1960s by overuse of pesticides containing chlorinated hydrocarbons, something from which populations have only recently recovered.

Infectious diseases monitoring network

Not only the effects of infectious diseases on birds, but also the diseases themselves are monitored by catching and ringing birds. Ringers take saliva, poop and blood samples from more than ten thousand birds every year for the nationwide surveillance of zoonotic infectious diseases. They already discovered three new viruses in the Netherlands over the past decade for which birds are an important host, but which can sometimes also make people sick. Usutu virus was discovered in 2016, five months before the mass mortality among blackbirds caused by the first outbreak. In 2020, West Nile virus was first detected in a wild warbler, and subsequently in other bird species and in mosquitoes. Thanks to this early detection, eight patients who were in hospital with hitherto unexplained severe symptoms could be adequately treated. Finally, in 2022, Sindbis virus was detected in a robin and then, partly retrospectively, in other bird species. Surveillance thus functions as an important “early warning” signal for zoonotic diseases, contributing to the integrated OneHealth approach to health.

Traffic density

RAS and other ringing projects on wheatears, whinchats, meadow pipits and other species living in dunes and sparse grasslands provide valuable insights into the effects of management on reproduction and survival. Intensive long-term ringing surveys of little owls and barn owls show the major impact of increased traffic density on survival. (Data from ringed birds are the only systematic source of traffic casualties on our roads.) For little owls, traffic seems to be an important explanation for the increased mortality of wandering young owls in autumn and winter. For barn owls, the study led to several practical measures to reduce the high number of traffic casualties. For instance, on the road sections where most ringed barn owls were found dead, special hectometric bollards are placed on which the owls cannot perch. They then move to higher lookouts, significantly reducing the chance of being hit by a car when flying away.

Birds are looking colourful

Vogeltrekstation is also increasingly the central collection point for sightings of birds with colour marks, such as coloured leg rings and sometimes collars that provide many more sightings than metal rings alone. Together with our partners, we run the world's largest website where thousands of observers can enter their sightings of colour-marked birds: submit.cr-birding.org. There, they can instantly see where else the birds have been seen during their lifetime. To do so, most observers use the linked BirdRing app, which allows them in the field to read everything about the birds they have seen. The researchers behind the nearly two hundred connected projects get the sightings added to their database automatically and in the right format.

Geese policy

The website and app are important in formulating policies for the international management of geese and other waterbirds. Over two million sightings of individually identifiable geese form the basis of policy. Every year, it determines what proportion of the population can be shot without jeopardising the favourable conservation status of the species, or whether a species should not be shot at all, and in which places protection zones should be established to save a species from extinction. The successful tandem of website and app and the management of the large amount of data they generate are co-funded by the Ministry of LVVN, the province of Fryslân and the Faunabeheereenheid Noord-Holland. The examples show that Vogeltrekstation's scientific infrastructure facilitates and initiates a motley array of research initiatives, with the use of individual bird marks at its core. Techniques to track birds, meanwhile, are becoming increasingly sophisticated. But the simple, inexpensive, non-burdensome metal bird ring with unique number is far from becoming absolete. In all likelihood, this survey method will survive into the next century.

This is the fifth article in a series on 70 years of ecological research at the Netherlands Institute of Ecology (NIOO-KNAW). Every edition features another line of research. Find out more about 70 years of ecology here.

This article also appeared in the May issue of Vakblad Natuur Bos Landschap.