The world's most spoken language is...Terpene

The world's most spoken language is...Terpene

If you’re small, smells are a good way to stand out. A team of researchers led by the Netherlands Institute of Ecology (NIOO-KNAW) has demonstrated for the first time that two different types of micro-organisms – bacteria and fungi – use fragrances, known as terpenes, to hold conversations. And that’s not all. “We actually believe that terpenes are the most popular chemical medium on our planet to communicate through.”

The most used language in the world? Think again, it’s probably ‘Terpene’! Research by microbial ecologists from NIOO and their colleagues has demonstrated that two very different groups of micro-organisms use fragrances to communicate with each other, the most common type being terpenes.

In only one gram of soil billions of micro-organisms are thriving, so that makes many ‘speakers’. On top of that: this ‘chemical communication’ will probably work for a whole bunch of other life forms as well. This is what the research team discovers in Scientific Reports, a relatively new journal from the Nature family.

A firm conversation

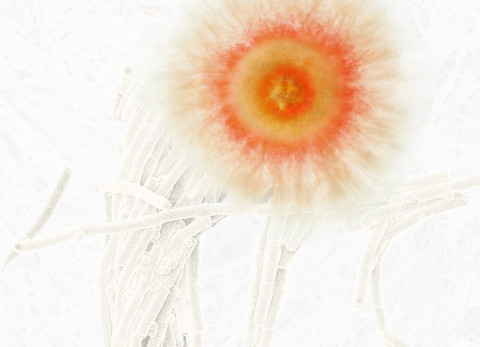

The researchers have demonstrated that bacteria and fungi do in fact respond to each other. In other words: they can hold conversations. Group leader Paolina Garbeva explains: “Serratia, a soil bacterium, can ‘smell’ the fragrant terpenes produced by Fusarium, a plant pathogenic fungus. It responds by becoming motile and producing a terpene of its own.”

The researchers established this by studying which genes were switched ‘on’ by the bacterium, which proteins it began to produce and which fragrance. Or, in more fancy terms: by using transcriptomic, proteomic and metabolomic techniques. “Such fragrances – or volatile organic compounds – are not just some waste product, they are instruments targeted specifically at long-distance communication between these minute fungi and bacteria.”

But how widespread is this ‘language of smells’? Pathogenic soil fungi such as Fusarium also have an effect aboveground, where they make plants sick. Can they communicate with those plants? Garbeva: “We have known for some time that plants and insects use terpenes to communicate with each other. But we’ve only just begun to realise that it’s actually much wider. There is a much larger group of ‘Terpene-speakers’: micro-organisms.”

Fungi, protists, bacteria, and even higher animals. Terpenes act as pheromones – chemical signals used by animals – which makes them a regular ingredient of perfumes. So it’s likely that the language of terpenes forms a vast chemical communications network indeed.

Multilingual

Terpenes are by no means the only volatile organic compounds that are in for a good chat. The researchers found others as well: in the soil, for instance. Garbeva’s PhD student Ruth Schmidt, the first author of the article, adds: “Organisms are multilingual, but ‘Terpene’ is the one that’s used most often.”

Who knows, maybe without realising it we are native speakers too?

_____________________________________________________________________________________

With more than 300 staff members and students, NIOO is one of the largest research institutes of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (KNAW). The institute specialises in water and land ecology. As of 2011, the institute is located in an innovative and sustainable research building in Wageningen, the Netherlands. NIOO has an impressive research history that stretches back 60 years and spans the entire country, and beyond.

More information:

- Research group leader Dr Paolina Garbeva, dept.of Microbial Ecology NIOO-KNAW, tel. +31-6-24660677 / +31-317-473492, p.garbeva@nioo.knaw.nl

- Science information officer Froukje Rienks, NIOO-KNAW, tel +31-6-10487481 / +31-317-473590, f.rienks@nioo.knaw.nl

Image: Having a good conversation: soil fungus Fusarium and the unrelated soil bacteria. Only to be used in combination with this research and with source. Source: 21 Lux photography/Heike Engel.

If a higher resolution is needed (for print media), please contact Froukje Rienks (see above).

Funding agency NWO contributed to this research through a VIDI-grant awarded to Paolina Garbeva.